“SIX PHOTOGRAPHS” BY STEEL STILLMAN

(published in OSMOS Summer 2018)

*

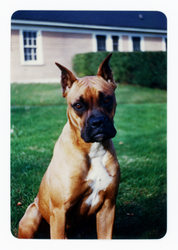

An early autumn morning in 1959. The boy, aged four, closes the apartment door and rides down the elevator with his father and the dog. The elevator man winks and smiles. They leave the building and walk several blocks in the crisp air, the boy, in short pants, shivering when the wind blows. The city and its bustling are familiar to him, its characters friendly, and the three of them stride like actors through a choreographed throng, which pinwheels apart as they pass by. It’s a performance he’s observed before, perched on a chair, looking down from the seventh floor.

*

The boy’s father went to see a psychiatrist to stop drinking. They sat across a large desk, on whose polished surface was a gun, supposedly loaded. The psychiatrist, whose name was Zabriskie, gave his father a choice. Me or the gun.

*

Recess takes place on the roof, behind the church’s high parapet. The space is laid out like a chessboard with a bell-tower, water tank, swing set, slide, and sandbox as its major pieces. Singly or in small groups, and obeying rules all their own, the children play in and around these elements with an assortment of toys and riding vehicles. The boy’s favorite is a red tractor with a steering wheel and pedals like a tricycle. He loves to maneuver it between the other children and around the enormous game-board. Today, another boy wants the tractor and runs behind him. But he’s not ready to yield. The other persists, and, catching hold of the boy, grabs his arm and bites hard. The action stops. It will be years before the mark disappears.

*

*

The meeting with Dr. Zabriskie came a day or two after what today would be called an intervention. The boy’s father had been on a bender. He’d been drinking for days, closed up in his study in the apartment on Sixty-seventh Street. The boy’s grandparents, who lived nearby, had been at their wits’ end. For too long, drinking had sabotaged every good thing that had come their son’s way. They’d tried everything to get him to stop. Pleading. Punishing. Rewarding. Nothing seemed to work. So they found Dr. Zabriskie, who’d been highly recommended, and organized a confrontation. They and the boy’s mother and uncle were there when the psychiatrist arrived. Everyone sat in the living room. Finally the boy’s father materialized from his lair, wearing pajamas. He looked awful and smelled worse. They said, Look, George, this may be your last chance.

*

His father chose the gun. Over the next few years, there were many more binges, often followed by weeks in drying-out hospitals. Usually, when he was released, he and the boy’s mother would celebrate. One time, they drove directly from the hospital to the airport, boarded a plane for Nassau and drank pitchers of martinis the whole way down.

*

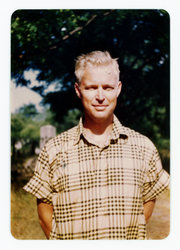

His mother is driving them – the boy, his younger sister and the dog – in the big old convertible. The top is down and sunlight flickers through the leaves. The car enters a gate that could be to a college or large estate, and proceeds up a long arcing driveway before stopping at an imposing edifice. The children wait in the backseat as their mother, in a light-blue summer dress, hurries up the steps, emerging a few minutes later with their father. He looks tanned and happy. He wears khaki trousers, a freshly ironed white shirt, its sleeves rolled up past his elbows, and penny loafers. His face is smooth and relaxed. He smells good.

*

They drive a little way down the driveway, away from the hospital building, but not off its grounds, to a spot by the side of a small lake. There they spread a red tartan picnic blanket and eat lunch from the hamper his mother has prepared. It is a sweet day.

*

There are plenty of roadside restaurants in the early ‘60s, but his family never stops at them. On car trips, when they need a break, especially in summertime, his father steers onto the grass at the edge of the highway and they take out the picnic blanket and hamper. There, with the buzz and flash of cars in the background, they eat their sandwiches and sip juice from cork-stoppered Thermos bottles. After discrete trips into the woods, they get back on their way.

*

His father always drives with his window down. Even in bad weather. Even in winter. It doesn’t seem to matter that the heater in the twenty-year-old car doesn’t work. Nor that the children are freezing, huddled in the backseat beneath a steamer rug, whose heavy gabardine outer layer covers a scratchy wool inner one. At least the dog provides some warmth.

*

The woman drives her battered sedan across the George Washington Bridge and heads north and west for nearly an hour, passing from highways onto gradually smaller roads, until turning left midway through a sleepy village. The car then winds up and down hills for several more miles, and along the shore of a clear lake before turning left again, this time between a pair of stone pillars. The house, made of wood and stone, was built at the end of the nineteenth century, and sits at the lake’s edge. It has deep, dark porches and two wings that embrace the driveway. The car bypasses the front door and disappears to the right behind a hedge. With a bang, a screen door slams and two children – the boy, now six, and his sister – race down the stone steps and across the gravel, their bathrobes flying, and leap into the arms of the slow-moving black woman, straightening up out of the car.

*

The boy grows up a watcher, a spy. In a house where the well-ordered hum of daily activity is periodically shattered by outbursts and violence, he practices silence and stealth. Much of his time is spent alone. When required to participate in family life, he does so warily, behaving at meals and on outings with practiced decorum and affability. Best to maintain a sunny demeanor. Mister Sunshine. Best not to cause trouble; the punishments are always harsh. Best to play along. He is praised for doing things well, for having good manners, for upholding his parents’ picture of him – and of themselves. But from within his solitude, he watches, reading the signs, alert to the first hint of trouble: the raised voice, the fist banging on the dinner table, the thrown glass.

*

*

After an early supper, the boy, again in short pants, is taking a ride with the nice man who runs the local kennel. The family’s dog is in the back of the station wagon. Their destination is nearly an hour away. As the kennel man drives, he jokes with the boy, and, for occasional emphasis, reaches across the wide front seat to squeeze the boy’s bare thigh. At first this seems like fun, but the squeezes become firmer. The boy says, Stop. That hurts. The man doesn’t seem to believe the boy because he keeps squeezing. Then he stops.

*

The glass hits the wall just below the mantle, its shards scattering across the hearth and rug. He has seen his father throw it, but it’s his mother’s voice he hears. Get out! Go on! How dare you come to the table drunk! After everything I’ve done for you! And in front of the children! Get out! His father lumbers out of his chair, his bathrobe falling open, and staggers from the room, bellowing, You get out! And take those goddamn children with you! Across the hall he goes and down the stairs to the basement, slamming the door behind him. The three of them sit, for a moment, in silence.

*

The room remains quiet. Then his mother says, It’s all right. Everything is going to be all right. But what is all right? He is barely seven. What exactlyis all right? Everything is still. Then Emma comes from the kitchen with a broom and dustpan. From the basement, just below where they are sitting, rumblings can be heard.

*

They are brothers, one eighteen months older than the other, teenagers from a comfortable, middle-class family in a leafy American suburb. Their father is a prosecutor and the boys are familiar with his cases. Indeed, they’ve developed antennae of their own, alert to hidden mystery, which lead them, again and again, to criminals operating just out of view. Despite the brothers’ age difference, they are equal partners, taking turns driving their yellow hotrod or leading the way into yet another dark redoubt. Their method is dialectic, with the question of one eliciting the inspiration of the other. And because they are diligent high school students, they are resourceful with technologies, as capable of cobbling together ad hoc mechanical devices as they are of performing forensic chemical analyses. As the stories approach their denouements, a moment invariably arrives when the boys – having gathered their evidence, and having the as-yet-unaware perpetrators under surveillance – bring their father and the police chief into their confidences. The grown-ups are incredulous. How can such villainy have gone undetected? But their astonishment soon turns to admiration, and the men and boys join forces to bring the matter to a close.

*

*

They are sitting in the front hall, waiting on a bench in front of the window. It is late evening, Labor Day, 1964, and outside everything is dark. The day has been hot and all the windows and doors are open to the cool air. The boy and his sister are alone. He is nine. School will start tomorrow. Though the children fidget, everything else, inside and out, is calm. The only sound is of crickets. Then, in the distance, a car is heard. A minute later, the children are illuminated by headlights, entering the gravel driveway. Their mother comes in and sits between them. The dog appears, his tail wagging. She has news for them.

*

In fourth grade, there is a new boy in his class. Except for the teacher, everyone else is familiar from last year. The new boy is strange. He is pale and neat, wears clunky brown shoes, and belts his pants high on his waist. But it quickly becomes clear that he is the smartest kid in the class.

*

She has come straight from the hospital. Their father had had a heart attack two days ago but he’d been getting better. The boy had visited him that morning. The hospital had been cool and quiet, the holiday having drained it of activity. Alone in a room, his father had been lying on his back inside an oxygen tent. There was stubble on his face and his eyes were closed. The boy had touched his hand.

*

How is it that he starts playing with Steven? Does it happen at school, out in the yard? Steven is uncoordinated and runs and throws balls like a girl. Maybe they start playing together on the day his mother invites Steven’s mother over for tea after school, and the boys run upstairs.

*

There is a photograph of the boy taken that Labor Day. He is wearing a white t-shirt and white shorts and stands by the net as ball boy for a tennis match. It is the men’s finals and in the background you can see spectators sitting in long rows. Some in the crowd know the boy and know what is going on down at the hospital. His eyes are downcast. He is waiting for the point to end.

*

The boy’s bedroom is large. Straight ahead, two windows with deep sills look out over the driveway and toward the trees and the grass beyond. Behind the boys is a door to the hall, actually a balcony, which overlooks an underused living room below. Wallpaper covers the bedroom walls. Its motif is of cut flowers, gathered in bouquets, bound not with ribbon but with snakes. Three snakes, in fact, to whom the boy has given names. Every night, when the lights are turned off, the snakes hover in the dark above his head.

*

*

The boy’s vision blurs. It’s hard to breathe. His mother is still talking. She’s not crying. She’s holding herself together, being brave for the children. She says that life will go on. She says that they can’t do anything about what’s happened – that they must sweep the past under the rug. He has not heard that phrase before. She tells the boy she’s counting on him, that he’s the man now and she needs him. She needs him to be strong and to take care of his sister. They must move forward.

*

In the middle of the room, on the worn brown rug, a set of wooden blocks is configured as a skyscraper. On the street in front, two painstakingly made model cars are parked, a convertible and a sedan. The cars are supposed to be perfect replicas of Detroit’s newest and best, but, on closer inspection, clumps of dried glue mar their plastic surfaces. Steven, who has been quietly taking it all in, rushes to the cars.

*

Inside the small suburban church, men in dark business suits roll the coffin to its place before the altar. The coffin reminds him of the wooden chest at the foot of his parents’ bed. Hymns are sung. He imagines his father inside, dressed in a dark blue suit, a white shirt and a striped tie, but minus his black shoes, which the undertaker had removed because his father was so tall. The dead man is six-foot-two.

*

In the shade of large maples and pines, a hole has been dug, its edges draped in fake grass.

*

He is an altar boy, sitting during hymns and prayers on a bench beside the organist, hidden from the congregation. The choir is across the way, on the opposite side of the altar, alternately standing to sing or sitting quietly. Among the choir is a man his father’s age, tall and handsome, with prematurely white hair. The resemblance to his father is uncanny, and, on Sunday after Sunday, the boy wonders if the man is indeed his dead father, come back in disguise to keep an eye on him, knowing every bad thing he’s done, and all the lies he’s beginning to tell.

*

*

When no one is around he sits at his mother’s dressing table and studies his reflection in its folding mirrors, the one in front and the other two that swing in from the sides. Sitting there, he sees himself as if he were someone else.

*

What if his father is not dead after all? What if the coffin that had stood just a few feet away, in front of this very altar, had been empty? What if – instead – his father had been a spy, and, having been assigned an important mission, had had to fake his own death? The man in the choir does not seem to notice him. Will not meet the boy’s eyes. Which means nothing, the boy decides. For what would happen if they were to acknowledge one another? The cover would be blown.

*

He sees a blond-haired boy in medium close-up. He sees the boy’s profile and the shape of the back of his head. He sees soft, rounded features, almost girl-like, and smooth, fair skin. In the quiet of the empty house, in the place where his mother invents her outward self, he experiments with her gestures, her poses, her expressions. He finds nothing of himself in the boy before him.

*

Sitting next to the organist, largely screened from view, the boy wears a red-and-white acolyte’s robe. The organist, a flowing black gown. The sermon is being delivered, and, except for the minister’s words, all is hushed in the church. The organist is a joker, a tease. He reaches over to tickle the boy, who giggles under his breath, not daring to make a sound. The organist’s hand climbs the boy’s thigh. Firmly, the boy pushes it away.

*

He is quite young, five or six, when he first sits in front of these mirrors. Occasionally, over the course of the next ten or more years, he’ll come back when no one is around. During that time he will grow taller, leaner. He will be sent away to school and return home for vacations. His hair will grow longer – it’s the late 1960s. His features will sharpen and his skin will change, its softness replaced first by pimples, then by patchy stubble. During these moments, he worries that no one will ever know who he is.

*

He is fourteen, at school in northern New England. He lives in a dormitory, in a room by himself under the eaves. One night after the lights are off, unable to sleep, he sits up in bed. Outside, the wind is blowing, and moonlight, filtering in through swaying trees, shines on a cast-iron radiator, whose vertical sections come to life. Shifting patterns of light and dark cohere into shapes, and suddenly he is watching JFK on the radiator-TV. The dead president’s black-and-white face is blurry, but it appears to be speaking. Is it really JFK? Or is it the boy’s own father? He can’t make out the words.

*

Four years later, the boy goes home one summer night with a girl he barely knows, who lives in a large apartment building. The next morning, looking out the window, he stares down on a chessboard playground he had all but forgotten. His gaze drops to his left forearm and the bite mark that had lingered well into his teens, but the impression is gone.

[END]